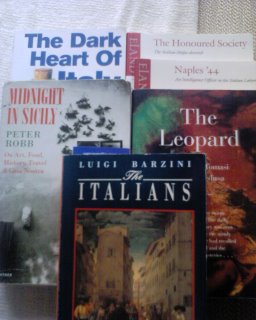

As the Italians tot up their ballots and ponder, no doubt with relish, the vista of a potential recount, The Midnight Court takes the opportunity to treat readers to the following perspicacious exerpts from Luigi Barzini’s explanation of how to succeed on the Latin peninsula. Having recommended his book,

The Italians: A Full-length Portrait, in Sunday’s post, I decided I’d better form a closer acquaintanceship with it myself. And I’m glad I did. Luigi’s voice is a compelling one; liberal, pragmatic, generous, wholly in tune with the condition of being human, not to mention scholarly and mature. One instinctively trusts his menchly, measured tone, which is reminiscent of Umberto Eco’s better moments but without the postmodern tics, even while suspecting that some of his strokes are that little bit broad. My only caveat is that The Italians was first published in 1964. Still the Italy it depicts is recognisably the one on which

Silvio Berlusconi and his henchme…, er, political allies are fighting to maintain their grasp.

(Lest Irish readers in the uber-modern

Tygger polity dare to feel insufferably smug about those crazy eyeties and their impossibly opaque politics, they should note the following example of our own facility with obscurantist power broking. Reading an interesting article on some aspect of the legislative process recently, I googled, as one does, its impressive barrister author, a former official in the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel,

Mr. Brian Hunt, and found his informative profile page at

Mason Hayes & Curran. He is the consultant at the firm who “

advises clients who have concerns about proposed and existing legislation, and the various ways in which they can seek to contribute to the shaping of that legislation.”

To seek to contribute to the shaping of legislation sure

sounds like a noble, thankless task; the patrician practice of succeeding generations of gentle plutocrats and not remotely a euphemistic description for special interest lobbying and an engagement with influence peddlers. I hasten to add that Mr. Hunt is certainly not doing anything wrong here, either morally or legally. He’s applying his hard-won knowledge for the benefit of his clients and employer. But the choice of language is interesting, to say the least.)

Starting with a brief survey of

la famiglia, the most immediate of the ever-increasing circles to which the wily Italian belongs, Barzini considers the pattern of competing, inter-leaved groups in that society, not least - but then again not the greatest - of which is the State itself. And there are wheels within that wheel too of course:

In Italy, powerful groups know no other limit to their power than the power of rival groups. They play a free-for-all game practically without rules and referee. Of course, the law is allegedly supreme; the apparatus of a quasi-modern State is visibly omnipresent, with its props, cast of characters, costumes, titles and institutions, but there are important differences between such dignitaries and organisations and what they are elsewhere.

Each branch of the State machinery in Italy is in reality a mighty independent power which must struggle sometimes for its existence, and usually for the prosperity of its protégés and subjects against all other rival branches of the State machinery: they fight savagely at times, but more often surreptitiously, exactly like private pressure groups, for a larger place in the sun, a bigger cut of the budget, more employees, a higher rank and wider prerogatives for their leaders.

The reference to costumes reminds me of the Italian railway station and the impact on it of the important concept of the bella figura. Maintaining the bella figura goes far beyond the bourgeois English notion of keeping up appearances and makes it next to impossible to distinguish an Italian platform steward from an admiral in command of an entire naval fleet. festooned, as such an officer must be, with epaulets and dripping in gold braid.

As both Berlusconi and Prodi will be well aware:The Prime Minister himself must have private backing of his own if he wants his orders to be obeyed, backing within his own party, within the bureaucracy, and within the Church (if he is a Christian Democrat) as he can scarcely depend on his constitutional authority alone.

The law in Italy is notoriously complex and contingent, more often used as just another weapon in the armoury of power than as an instrument of justice and deployed not so much with a view to achieving the immediate end of a litigious battle, but of tying up one’s opponent, shackling his resources and distracting his attention:Some sort of protection is therefore necessary for everybody. Even the little men with no ambition need ample help merely to be left alone.

And so: After much hoo-ing and ha-ing, several contested votes, a court case and, not least, a scary reference to civil war, Silvio has conceded defeat. Looks like it will be a bit of a "we haven't gone away you know" situation in the Italian parliament where it's avowed that the feck-acting will continue as the right fulfils its "moral duty" to bring down the government, promoting instability at this delicate juncture for their economy and society.

Why is that the right gets on everyone's case about duty while it is liberalism which has to do the decent thing in times of crisis/delicacy and bite its lip as the morally and credibility bankrupt on the right go about the business of fucking things up for everyone except their cronies?

After much hoo-ing and ha-ing, several contested votes, a court case and, not least, a scary reference to civil war, Silvio has conceded defeat. Looks like it will be a bit of a "we haven't gone away you know" situation in the Italian parliament where it's avowed that the feck-acting will continue as the right fulfils its "moral duty" to bring down the government, promoting instability at this delicate juncture for their economy and society.

Why is that the right gets on everyone's case about duty while it is liberalism which has to do the decent thing in times of crisis/delicacy and bite its lip as the morally and credibility bankrupt on the right go about the business of fucking things up for everyone except their cronies?